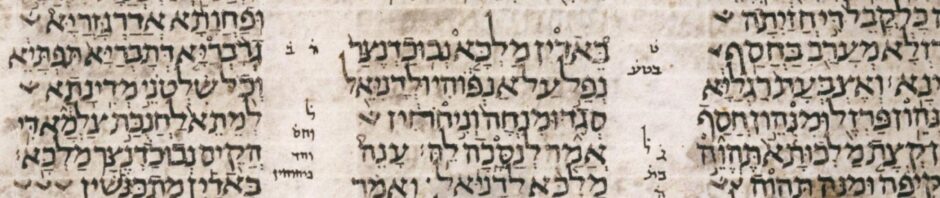

עָנֵ֤ה מַלְכָּא֙ וְאָמַ֣ר לְכַשְׂדַּיָּ֔א מִלְּתָ֖א מִנִּ֣י אַזְדָּ֑א הֵ֣ן לָ֤א תְהֹֽודְעוּנַּ֨נִי֙ חֶלְמָ֣א וּפִשְׁרֵ֔הּ הַדָּמִין֙ תִּתְעַבְד֔וּן וּבָתֵּיכֹ֖ון נְוָלִ֥י יִתְּשָׂמֽוּן׃

(Daniel 2:5)

The king answered and said to the Chaldeans, “The matter has departed from me: if you do not make known to me the dream and its interpretation, you shall be made into pieces, and your houses shall be turned into dung-heaps.”

Opening the Stone Door: A Glimpse into the Emphatic State

In the Aramaic of Daniel 2:5, we encounter a royal decree wrapped in sharp grammar. The verse begins with עָנֵ֤ה מַלְכָּא֙ (“The king answered”), but what demands special attention is the forceful use of the emphatic state, a hallmark feature of Aramaic nominal morphology. Unlike Biblical Hebrew, which employs the definite article הַ– to mark definiteness, Biblical Aramaic embeds definiteness into the noun’s form itself—through the emphatic state.

This article explores the emphatic state as used in this verse and offers a historical-linguistic journey through its significance, especially in contrast to Hebrew grammar. Let’s walk through the linguistic ruins left behind by Nebuchadnezzar’s threat and learn how grammar shapes imperial speech.

The Emphatic State in Action

Several emphatic forms appear in this verse:

- מַלְכָּא – “the king” (from מֶלֶךְ)

- מִלְּתָא – “the matter/word” (feminine emphatic)

- חֶלְמָא – “the dream”

- פִּשְׁרֵהּ – “its interpretation” (the base noun is emphatic in form though with a pronominal suffix)

- הַדָּמִין – “pieces” (emphatic plural)

- נְוָלִי – “dung-heap” (emphatic singular)

Each of these uses the Aramaic emphatic ending: –ָא for masculine singular, –ָתָא or –ָא for feminine singular, and –ִין for masculine plural (cf. הַדָּמִין).

Historical-Linguistic Perspective

The emphatic state originated in Imperial Aramaic and reflects earlier Semitic definiteness mechanisms that did not rely on separate articles. Over time, while Hebrew developed a prefixed definite article (הַ–), Aramaic evolved an inflectional strategy. This difference in strategy marks a profound divergence in how the two languages treat the semantics of specificity, familiarity, and topicality.

For example:

| Aramaic (Emphatic State) | Hebrew Equivalent | Literal Translation |

|---|---|---|

| מַלְכָּא | הַמֶּלֶךְ | the king |

| מִלְּתָא | הַדָּבָר | the word / matter |

| נְוָלִי | אַשְׁפָּה | dung-heap |

Emphatic, Absolute, and Construct: Aramaic’s Three States

Like other Semitic languages, Biblical Aramaic distinguishes between three states for nouns:

- Absolute state: the default form, indefinite (e.g., מֶלֶךְ – “a king”)

- Emphatic state: definite or specific, marked with endings (e.g., מַלְכָּא – “the king”)

- Construct state: used in genitive constructions (e.g., מַלְךְ in מַלְךְ בָּבֶל – “king of Babylon”)

In our verse, all the emphasized nouns function as definite, hence they appear in the emphatic state—even without a separate article. This makes Aramaic highly efficient in packaging definiteness within morphology, rather than using syntactic markers.

Usage in Royal and Legal Discourse

The emphatic state dominates Daniel’s court scenes because it reflects official, elevated, and precise diction. Just as legal English uses “the party of the first part,” Aramaic uses מִלְּתָא rather than simply “a matter.” The king isn’t rambling—he’s issuing threats through rigidly emphatic forms.

Why It Matters for Aramaic Readers Today

For modern readers, recognizing the emphatic state is essential for interpreting Biblical Aramaic. It communicates definiteness and sometimes topicality, impacting both translation and exegesis. Consider this difference:

- חֶלְמָא – “the dream” (a known, specific dream)

- חֶלְם – “a dream” (any dream; indefinite)

Failing to notice these forms may lead to misreading whether something was assumed knowledge or a new introduction in the narrative.

Closing the Palace Gate

In Daniel 2:5, grammar and monarchy intertwine. The king’s threat to dismember and demolish is framed with emphatic nouns, emphasizing finality, fear, and control. Understanding the emphatic state not only opens the linguistic doors of Aramaic—it reveals how definiteness encoded power, precision, and imperial prerogative in ancient texts.