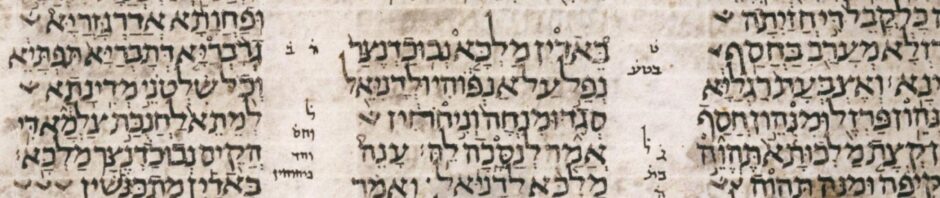

וְדָ֣נִיֵּ֔אל עַ֖ל וּבְעָ֣ה מִן־מַלְכָּ֑א דִּ֚י זְמָ֣ן יִנְתֵּן־לֵ֔הּ וּפִשְׁרָ֖א לְהַֽחֲוָיָ֥ה לְמַלְכָּֽא׃

(Daniel 2:16)

And Daniel went in and requested from the king that time may be given to him, and that he might declare the interpretation to the king.

The form יִנְתֵּן in Daniel 2:16 provides a vivid example of how Biblical Aramaic uses verbal morphology and syntax to frame a diplomatic request. While translations often render this as “that time may be given,” the underlying grammar is formally active, with the passive nuance emerging from syntax and context rather than morphology.

Parsing יִנְתֵּן

- Root: נ־ת־ן (“to give”)

- Stem: Peʿal (G-stem)

- Form: Imperfect, 3rd masculine singular

- Voice: Active (functioning in a jussive/optative sense within a request clause)

- Aspect: Incomplete, expressing potential or future action

- Subject: Implied — the king

Table: Morphological and Functional Features of יִנְתֵּן

| Feature | Description | Effect in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stem | Peʿal (simple/basic) | Base meaning “to give” |

| Aspect | Imperfect | Non-completed action, expressing potentiality |

| Voice | Active | Morphologically active; passive nuance from object-fronting and omission of subject |

| Function | Jussive/optative in subordinate clause | Softens the request, showing deference |

Why This Is Not a True Passive

While English translations often render this as passive (“may be given”), the Aramaic form is not morphologically passive. Biblical Aramaic lacks a productive niphʿal equivalent; instead, it often uses active peʿal forms in contexts where the subject is implied and the object is fronted, producing a passive-like sense in translation. Here, the implied subject is the king, and the fronted object זְמָן creates the effect of a formal petition.

Syntax and Court Etiquette

The clause דִּי זְמָן יִנְתֵּן־לֵהּ is introduced by דִּי (“that”), marking a subordinate clause of request or purpose. In Ancient Near Eastern court speech, direct imperatives to a monarch could be perceived as disrespectful. By embedding the verb in a subordinate clause with a jussive sense, Daniel aligns with royal protocol, avoiding the presumption of a direct command.

Comparison with Biblical Hebrew

In Biblical Hebrew, a similar polite request would typically use the niphʿal imperfect (יִנָּתֵן) to mark the passive morphologically. Since Biblical Aramaic lacks this form, it achieves a comparable effect syntactically: the active imperfect with an implied subject and fronted object conveys the same deference and tentativeness.

Grammar in Service of Diplomacy

Here, grammar and rhetoric work together. The imperfect form keeps the request open-ended, the implied subject honors the king’s agency, and the word order foregrounds the urgency of the “time” requested. In Daniel’s audience with the king, the choice of form is not accidental — it is a calculated blend of grammatical structure and courtly respect.