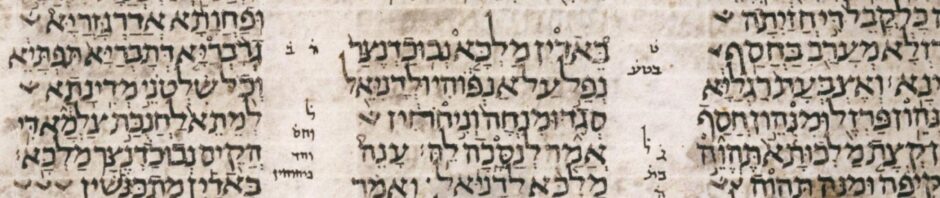

וּמִלְּתָ֨א דִֽי־מַלְכָּ֤ה שָׁאֵל֙ יַקִּירָ֔ה וְאָחֳרָן֙ לָ֣א אִיתַ֔י דִּ֥י יְחַוִּנַּ֖הּ קֳדָ֣ם מַלְכָּ֑א לָהֵ֣ן אֱלָהִ֔ין דִּ֚י מְדָ֣רְהֹ֔ון עִם־בִּשְׂרָ֖א לָ֥א אִיתֹֽוהִי׃

(Daniel 2:11)

And the thing that the king demands is difficult, and there is no other who can declare it before the king—except the gods, whose dwelling is not with flesh.”

A Double Negation with Divine Implication

Daniel 2:11 continues the Chaldeans’ protest, intensifying their argument through two carefully deployed existential negatives using the Aramaic particle אִית. First, they deny the existence of any other human who can reveal the king’s dream (אָחֳרָן לָ֣א אִיתַ֔י), then they make a theological claim: the only beings who could possibly answer (אֱלָהִין) do not dwell among mortals (עִם־בִּשְׂרָ֖א לָ֥א אִיתֹֽוהִי).

This verse provides a rich field for grammatical, theological, and existential analysis, where grammar and metaphysics intertwine.

Morphology and Syntax: Parsing אִיתַי and אִיתֹהִי

Let’s examine both existential forms in the verse:

| Phrase | Form | Literal Translation |

|---|---|---|

| לָ֣א אִיתַ֔י | Existential negation + emphatic suffix | “There is not (another)” |

| לָ֥א אִיתֹֽוהִי | Existential negation + 3ms suffix | “He is not (present)” or “It is not among” |

אִיתַי here includes the emphatic pronominal suffix -ַי, often interpreted as intensifying the assertion (“truly there is”). אִיתֹהִי contains the third masculine singular suffix -הִי, which in Biblical Aramaic can refer back to a plural noun like אֱלָהִין (gods) when functioning as a collective or abstract entity. Thus, the Chaldeans say: “there is no other (human),” and “the gods are not with flesh.”

Theology through Syntax: Gods and Flesh

The final clause of the verse is both theological and ontological:

אֱלָהִין דִּ֚י מְדָ֣רְהֹ֔ון עִם־בִּשְׂרָ֖א לָ֥א אִיתֹֽוהִי – “The gods, whose dwelling is not with flesh.”

Key elements:

- מְדָ֣רְהֹ֔ון – “their dwelling”; this is a noun, not a participle. The base noun is מְדָר (“dwelling” or “abode”), with the 3mp pronominal suffix -הוֹן (“their”). It derives from the root ד־ו־ר (“to dwell”), and is related in meaning to residence or habitation. It does not carry verbal aspect or participial force.

- עִם־בִּשְׂרָא – “with flesh” (i.e., among mortals or humans)

- לָ֥א אִיתֹֽוהִי – “he/it is not (present)”; the 3ms suffix likely refers back to מְדָרְהוֹן, meaning “their dwelling is not [among flesh].”

The phrase doesn’t merely say “the gods don’t live here” — it encodes a metaphysical separation between divine beings and corporeal humans. The Aramaic existential form lends this statement weight: it is not an action verb, but a state of being denial.

Comparison with Hebrew and Broader Semitics

Hebrew might say: אֵין אֱלֹהִים שֶׁדִּירָתָם עִם בָּשָׂר — “There are no gods whose dwelling is with flesh.” But Aramaic does something stronger: it uses אִית to assert or deny existence as a whole condition, not merely a subject-action-object construction.

This use of אִיתֹוהִי demonstrates how suffixes interact with existential particles to give precise theological nuance. The gods are not “here” — not physically, not relationally, not ontologically — and that’s why the Chaldeans cannot fulfill the king’s demand.

The Chaldeans’ Final Defense

Verse 11 concludes a three-part defense:

- יַקִּירָ֔ה – “The matter is difficult.”

- אָחֳרָן לָ֣א אִיתַ֔י – “There is no other [person] who can declare it.”

- עִם בִּשְׂרָא לָא אִיתֹֽוהִי – “The gods do not dwell with flesh.”

This is not mere refusal — it draws a stark boundary between heaven and earth. The Chaldeans use legal, philosophical, and theological grammar to defend their human limitations while alluding to divine transcendence.

When Absence Speaks: The Power of לָא אִית

Daniel 2:11 uses existential negation not only to deny human capacity but to affirm divine aloofness. The rare form אִיתֹוהִי packs theological density into a single word. The Chaldeans’ claim is not just “we cannot”—it’s “no one can,” and even the gods do not condescend to dwell among mortals.

In Biblical Aramaic, absence can speak louder than action. And לָא אִית becomes the grammatical cry of limitation — and of coming revelation.