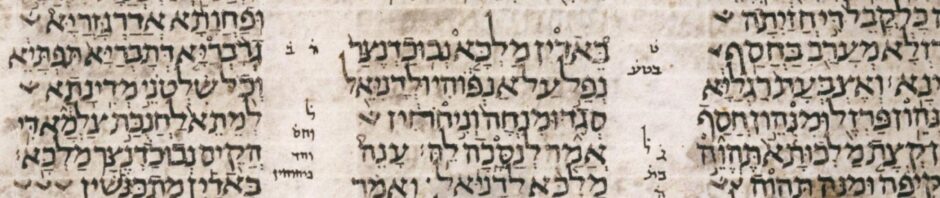

עָנֵ֤ה מַלְכָּא֙ וְאָמַ֔ר מִן־יַצִּיב֙ יָדַ֣ע אֲנָ֔ה דִּ֥י עִדָּנָ֖א אַנְתּ֣וּן זָבְנִ֑ין כָּל־קֳבֵל֙ דִּ֣י חֲזֵיתֹ֔ון דִּ֥י אַזְדָּ֖א מִנִּ֥י מִלְּתָֽא׃

(Daniel 2:8)

The king answered and said, “Surely I know that you are buying time, because you have seen that the matter has gone from me.”

A King’s Suspicion and a Syntax of Accusation

In Daniel 2:8, King Nebuchadnezzar levels an accusation with sharp grammar. The phrase עִדָּנָ֖א אַנְתּ֣וּן זָבְנִ֑ין (“you are buying time”) introduces a key syntactic and morphological feature of Biblical Aramaic: the participle</b. Used here to express an ongoing, present-tense action, the participle serves as both a grammatical tool and a rhetorical dagger.

This article focuses on the participial form זָבְנִין and its use to express current intentional action, contrasting it with finite verb forms and exploring its significance in Aramaic discourse.

Morphological Profile: זָבְנִין (“you are buying”)

The verb זָבְנִין comes from the root ז־ב־ן meaning “to buy” or “to purchase.” Let’s break down the form:

- Root: ז־ב־ן

- Stem: Peʿal (basic active stem)

- Form: Masculine plural participle

- Voice: Active

- Agreement: Subject = אַנְתּוּן (“you [plural]”)

- Translation: “you are buying” (i.e., deliberately stalling)

In Biblical Aramaic, the participle often functions as a present tense or a descriptive continuous form, especially in contrast to the perfect (past) or imperfect (future/potential) forms. The king isn’t accusing them of having bought time—he is accusing them of doing it now.

Syntactic Construction: Predicate Participle + Pronoun

The structure אַנְתּוּן זָבְנִין is a classic Aramaic predicate sentence in which the participle acts as the predicate and the pronoun אַנְתּוּן (“you [pl.]”) functions as the subject:

| Phrase | Function | Tense |

|---|---|---|

| אַנְתּוּן | Subject pronoun (you plural) | — |

| זָבְנִין | Participle predicate (“are buying”) | Present / Continuous |

This syntactic construction is similar to Biblical Hebrew’s use of participles in presentative clauses (e.g., אַתֶּם קוֹנִים “you are buying”), but Aramaic leans more heavily on the participle in both narrative and legal settings for present actions.

Rhetoric of the Present: Participles as Accusation

The participle’s aspectual force here carries a tone of immediacy and exposure. The king accuses them not just of a general tendency, but of an ongoing, visible strategy. The action is happening right now, as they speak:

- עִדָּנָ֖א אַנְתּוּן זָבְנִין – “You are buying time.”

- דִּ֣י חֲזֵיתֹ֔ון – “because you have seen…” (perfect)

- דִּ֥י אַזְדָּ֖א מִנִּ֥י מִלְּתָֽא – “that the matter is gone from me.”

We thus see the participle used against a background of perfect verbs that indicate completed past realizations (they’ve already seen that the king forgot the dream), while the participle shows their current evasive behavior.

Historical Perspective: Participles in Courtly Aramaic

In Imperial Aramaic and the Aramaic of the Achaemenid period, participles commonly appear in direct speech and legal discourse to describe current status or habitual behavior. Daniel 2:8 follows this usage precisely, placing the participial construction in the mouth of a suspicious and increasingly hostile king.

Notably, this contrasts with Aramaic narrative verbs, which are typically expressed with perfect or wayyiqtol-style sequential verbs. Participles are reserved for non-sequential, state-describing clauses or rhetorical emphasis—as we see here.

The King’s Present Accusation

Through the present-tense participle זָבְנִין, Nebuchadnezzar doesn’t just report—he accuses. Biblical Aramaic participles, particularly in predicate position, give speakers a powerful tool for framing perception. The king claims knowledge (יָדַ֣ע אֲנָ֔ה), and uses participial grammar to freeze the advisors’ manipulation in the present tense. This is language as spotlight: “I see what you are doing.”

In Biblical Aramaic, the participle is more than a tense—it is a tool of immediacy, confrontation, and sometimes, condemnation.