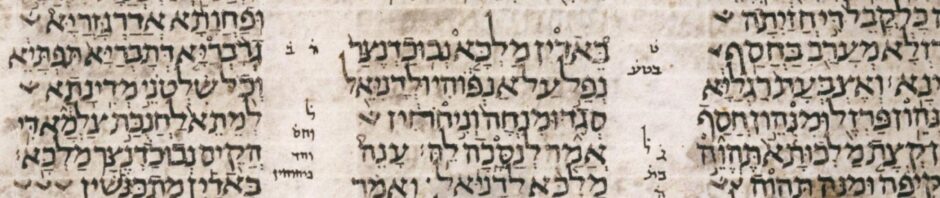

וְהֵ֨ן חֶלְמָ֤א וּפִשְׁרֵהּ֙ תְּֽהַחֲוֹ֔ן מַתְּנָ֤ן וּנְבִזְבָּה֙ וִיקָ֣ר שַׂגִּיא תְּקַבְּל֖וּן מִן־קֳדָמָ֑י לָהֵ֕ן חֶלְמָ֥א וּפִשְׁרֵ֖הּ הַחֲוֹֽנִי׃

(Daniel 2:6)

But if you show the dream and its interpretation, you shall receive gifts and a reward and great honor from me; therefore show me the dream and its interpretation.

Unlocking Conditional Clauses with הֵן and לָהֵן

Daniel 2:6 offers a rich illustration of conditional syntax in Biblical Aramaic, featuring both the modal particle הֵן (“if”) and its consequence marker לָהֵן (“therefore”). This verse is not merely a rhetorical repetition; it is a masterclass in how Aramaic structures conditional logic, expectations, and royal demands.

In Biblical Hebrew, conditionals typically begin with אִם, while results may be implied or introduced with אָז. Aramaic, however, has its own set of conditional markers, and these have specific syntactic and pragmatic functions.

Particle Focus: הֵן (“If”)

The particle הֵן introduces a protasis (conditional clause) and is roughly equivalent to Hebrew אִם. In Daniel 2:6, we read:

וְהֵן חֶלְמָ֤א וּפִשְׁרֵהּ֙ תְּֽהַחֲוֹ֔ן – “But if you show the dream and its interpretation…”

This clause is grammatically dependent. It sets up the condition upon which the apodosis (result clause) is based. Note that תְּֽהַחֲוֹן (“you show”) is in the imperfect (prefix) form, reflecting potential or future action—a perfect match for conditional modality.

Particle Focus: לָהֵן (“Therefore”)

Later in the same verse, after promising gifts and honor, the king repeats his demand:

לָהֵ֕ן חֶלְמָ֥א וּפִשְׁרֵ֖הּ הַחֲוֹֽנִי – “Therefore, show me the dream and its interpretation.”

Here, לָהֵן functions as an inferential or consequential particle: “so,” “then,” or “therefore.” This word is often overlooked in syntactic analysis, yet it provides coherence and flow to Aramaic arguments, similar to Greek οὖν or Latin igitur.

Conditional Syntax in Context

| Clause | Aramaic Particle | Function |

|---|---|---|

| וְהֵן חֶלְמָא… תְּֽהַחֲוֹן | הֵן | Condition (“if”) |

| מַתְּנָ֤ן וּנְבִזְבָּה֙… תְּקַבְּל֖וּן | (—) | Result (apodosis, implied) |

| לָהֵן חֶלְמָ֥א… הַחֲוֹֽנִי | לָהֵן | Inference (“therefore”) |

Comparison with Hebrew and Targumic Usage

While Hebrew employs אִם and often leaves results unstated or introduces them loosely, Aramaic is structurally more rigid in formal registers. The use of הֵן and לָהֵן allows Aramaic to bind protasis and apodosis explicitly, which is particularly useful in administrative, legal, and prophetic discourse.

Targum Onkelos often preserves these structures when translating Hebrew narratives. However, in freer Targumim (e.g., Jonathan), אִם is often translated אֵן or הֵן while לָהֵן marks divine actions or consequences.

Pragmatic Power in Courtroom Speech

Daniel 2:6 isn’t simply syntactic; it’s royal pragmatics. The king structures his demand with clear conditions and inferred rewards, adding rhetorical force by repeating the condition with לָהֵן. The result: the threat becomes a negotiation. These particles mark the edges of royal tolerance.

Grammar in the King’s Bargain

In the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, grammar was not a neutral tool—it was a weapon. The careful use of הֵן and לָהֵן gave structure to ultimatum and persuasion alike. Biblical Aramaic, in its conditional syntax, offers a glimpse into how ancient empires reasoned, warned, and rewarded—all in the shape of a sentence.