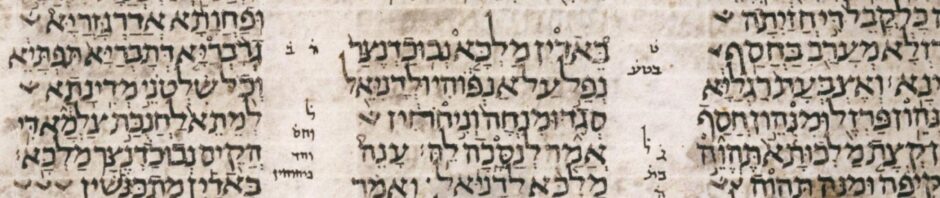

עֲנֹ֨ו כַשְׂדָּיָּא קֳדָם־מַלְכָּא֙ וְאָ֣מְרִ֔ין לָֽא־אִיתַ֤י אֲנָשׁ֙ עַל־יַבֶּשְׁתָּ֔א דִּ֚י מִלַּ֣ת מַלְכָּ֔א יוּכַ֖ל לְהַחֲוָיָ֑ה כָּל־קֳבֵ֗ל דִּ֚י כָּל־מֶ֨לֶךְ֙ רַ֣ב וְשַׁלִּ֔יט מִלָּ֤ה כִדְנָה֙ לָ֣א שְׁאֵ֔ל לְכָל־חַרְטֹּ֖ם וְאָשַׁ֥ף וְכַשְׂדָּֽי׃

(Daniel 2:10)

The Chaldeans answered before the king and said, “There is no man on earth who is able to declare the matter of the king; for no great and powerful king has ever asked such a thing of any magician, conjurer, or Chaldean.”

“There Is Not” — Denying Existence with לָא־אִיתַי

In Daniel 2:10, the Chaldeans respond with a structured protest. Their sentence opens with the phrase לָֽא־אִיתַ֤י אֲנָשׁ֙ — “There is no man.” This construction showcases an important syntactic and semantic feature of Biblical Aramaic: the use of the particle אִית to indicate existence, and לָא־אִית to negate it.

This article explores the morphology, function, and syntax of אִית, comparing it with its Hebrew counterpart and showing how its usage shapes the logic and emphasis of the Chaldeans’ reply.

Parsing the Existential Clause: לָא־אִיתַ֤י אֲנָשׁ֙ עַל־יַבֶּשְׁתָּ֔א

The key phrase reads literally as:

“There is not a man upon the dry land [i.e., earth].”

Let’s parse it:

- לָא־אִיתַי – “There is not” (compound of negation + existential particle)

- אֲנָשׁ – “a man”

- עַל־יַבֶּשְׁתָּא – “on the dry land” (emphatic form, i.e., “on earth”)

אִית is a frozen form of the verb “to be” used exclusively to assert existence. It is always used impersonally — no subject is inflected into the verb — and it typically appears in nominal clauses without a true verb. In this case, it is negated by לָא and attached to the pronominal suffix ־ַי for emphasis, making it אִיתַי.

Comparison with Hebrew: יֵשׁ / אֵין

In Biblical Hebrew, existence is typically expressed with יֵשׁ (“there is”) and אֵין (“there is not”). Aramaic uses אִית (“there is”) and לֵית or לָא־אִית (“there is not”). In Daniel 2:10, לָא־אִיתַי is chosen, emphasizing the complete nonexistence of a capable man anywhere on earth.

| Concept | Biblical Hebrew | Biblical Aramaic |

|---|---|---|

| There is | יֵשׁ | אִית |

| There is not | אֵין | לֵית or לָא אִית |

This structure also appears in other Aramaic sections of Daniel (e.g., Daniel 3:29), reinforcing the existential particle’s consistency across speakers and rhetorical contexts.

Syntactic Force in Courtly Speech

The structure לָא־אִיתַי אֲנָשׁ עַל־יַבֶּשְׁתָּא serves as the topic-comment foundation of the Chaldeans’ defense. They begin not with themselves, but with a universal statement of impossibility: no one, anywhere, can do what the king asks.

This clause is then expanded with a relative construction:

- דִּ֚י מִלַּ֣ת מַלְכָּ֔א יוּכַ֖ל לְהַחֲוָיָ֑ה – “who is able to declare the matter of the king”

The participial verb יוּכַל (“is able”) follows the standard Peʿal imperfect form and confirms that the assertion is not just descriptive, but logical and modal: no man exists who could (not who would).

Rhetorical Weight: From Impossibility to Legal Precedent

The Chaldeans move from existential denial to judicial precedent:

“No great and powerful king has ever asked such a thing…”

Here, the construction לָ֣א שְׁאֵ֔ל is a Peʿal perfect, showing a completed (and never-happened) action. The combination of:

- כָל־מֶ֨לֶךְ֙ רַ֣ב וְשַׁלִּ֔יט – “any great and powerful king”

- with כִדְנָה – “such a thing”

presents a powerful historical defense: not only is the request impossible, it is also unprecedented.

When Grammar Draws a Line

Daniel 2:10 is not just a response — it is a carefully constructed line of defense. The Chaldeans employ:

- Existential negation (לָא־אִיתַי) to reject feasibility

- Modal logic (יוּכַל) to highlight incapacity

- Historical precedent (לָ֣א שְׁאֵ֔ל) to frame the king’s request as irrational

In Biblical Aramaic, the particle אִית is deceptively small — yet capable of carrying the full weight of ontological denial. Here, it becomes the fulcrum of resistance: “There is not. There has never been. There cannot be.”