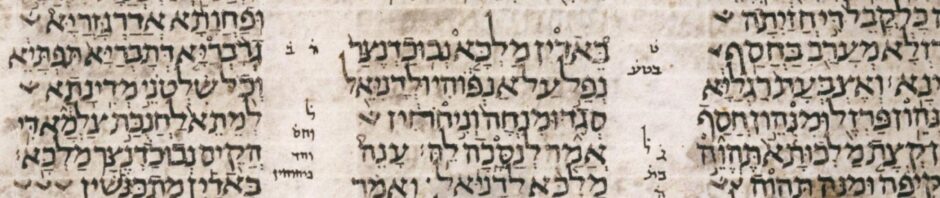

וַֽיְדַבְּר֧וּ הַכַּשְׂדִּ֛ים לַמֶּ֖לֶךְ אֲרָמִ֑ית מַלְכָּא֙ לְעָלְמִ֣ין חֱיִ֔י אֱמַ֥ר חֶלְמָ֛א לַעֲבְדָּ֖יךְ וּפִשְׁרָ֥א נְחַוֵּֽא׃

(Daniel 2:4b)

And the Chaldeans spoke to the king in Aramaic, “O king, live forever! Tell the dream to your servants, and we will declare the interpretation.”

Opening the Aramaic Gateway

This verse marks a major structural shift in the Book of Daniel. From Daniel 2:4b through 7:28, the biblical text transitions from Hebrew into Aramaic, the diplomatic and imperial lingua franca of the Babylonian and Persian empires. What better place to begin exploring Aramaic word order than at the very verse that introduces this new linguistic register?

In Daniel 2:4b, the Chaldeans address the king in formal speech. The grammar reveals not only stylistic features of royal address but also significant syntactic differences from Biblical Hebrew. Let’s unpack how Aramaic sentence structure operates here—and how it reflects the broader typology of Northwest Semitic languages.

Dissecting the Syntax: Clause by Clause

1. Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) Shift

The opening verb וַיְדַבְּרוּ (“and they spoke”) reflects the expected VSO structure in both Hebrew and Aramaic narrative prose. But once the speech begins, Aramaic demonstrates greater syntactic flexibility than Hebrew:

- מַלְכָּא לְעָלְמִין חֱיִי — “O king, live forever” places the subject first, then adverbial phrase, then verb. This is a nominal vocative followed by an imperative form with appended adverbial phrase (“forever”).

- אֱמַר חֶלְמָא לַעֲבְדָּיךְ — “Tell the dream to your servants” retains VSO: verb (אֱמַר), direct object (חֶלְמָא), indirect object (לַעֲבְדָּיךְ).

2. The Role of Fronting and Focus

Aramaic allows flexibility in word order for pragmatic reasons, such as focus or emphasis. For example:

- חֶלְמָא precedes לַעֲבְדָּיךְ, possibly for emphasis: “The dream—tell to your servants.”

- In contrast, Hebrew might have been more rigid in maintaining VSO even in non-narrative speech.

Comparative Glance: Hebrew vs. Aramaic Syntax

| Feature | Biblical Hebrew | Biblical Aramaic |

|---|---|---|

| Default Word Order | VSO (Verb-Subject-Object) | VSO, but allows SVO and OVS for emphasis |

| Imperative + Object | Verb tends to lead | Object may be fronted (e.g., חֶלְמָא before verb) |

| Vocative Phrases | Rare and usually embedded in syntax | Free-standing vocatives like מַלְכָּא are common |

The Diplomacy of Syntax: Why It Matters

In royal court contexts, Aramaic syntax is often stylized to reflect hierarchy and deference. Placing the king’s title first (מַלְכָּא) and isolating it from the main clause (חֱיִי) gives it elevated prominence. Likewise, the imperative אֱמַר follows a softened structure: the request is made after honorific greeting and with the object preposed—a subtle diplomatic move.

These features are not merely stylistic. They reflect sociolinguistic pressures of Persian-era bureaucracy and Babylonian ceremonial court speech, where clarity, honor, and obedience were encoded into grammar.

Masoretic Traces and Vocalization Nuance

The Masoretes carefully preserved the vowel system that distinguishes חֶלְמָא (the noun “dream”) from similar triliteral roots. The ending -ָא (aleph with qamats) is characteristic of the emphatic state in Aramaic, the functional equivalent of the Hebrew definite article הַ. It functions here as: “the dream”, not just “a dream.”

This state also affects agreement and syntactic anchoring, particularly when object fronting is used, as it is here.

Syntax as Ceremony: A Grammatical Bow

Daniel 2:4b is not just the start of Aramaic prose in the Tanakh—it is a parade of imperial formality rendered in syntax. The subtle shift of object position, the balancing of imperatives with flattery, and the open vocative reveal how Biblical Aramaic embeds etiquette within grammar. Understanding its word order not only illuminates Aramaic linguistics but also opens a window into ancient diplomacy and divine dreams.