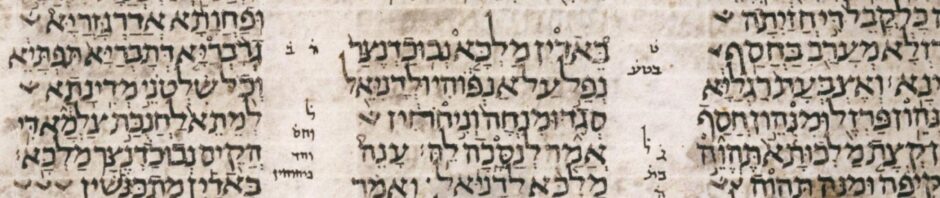

כָּל־קֳבֵ֣ל דְּנָ֔ה מַלְכָּ֕א בְּנַ֖ס וּקְצַ֣ף שַׂגִּ֑יא וַאֲמַר֙ לְהֹ֣ובָדָ֔ה לְכֹ֖ל חַכִּימֵ֥י בָבֶֽל׃

(Daniel 2:12)

Because of this, the king became furious and very angry, and he ordered to destroy all the wise men of Babylon.

From Protest to Punishment

Daniel 2:12 marks a turning point in the narrative. After the Chaldeans admit they cannot fulfill the king’s demand (Daniel 2:10–11), Nebuchadnezzar responds with a surge of royal rage. The Aramaic construction in this verse combines syntactic economy with emotional escalation. In just one sentence, the author conveys the king’s inner upheaval and outward decree using precise verbal forms and participles.

This article analyzes the binyanim (verbal stems), word order, and grammar of this verse to uncover how Aramaic expresses royal volition, wrath, and decree.

Morphological Breakdown

- כָּל־קֳבֵ֣ל דְּנָ֔ה – “Because of this”

- כָּל־קֳבֵל: “because of” (compound preposition)

- דְּנָ֔ה: demonstrative pronoun, emphatic “this”

- מַלְכָּ֕א – “the king” (emphatic state, subject of the sentence)

- בְּנַ֖ס – “he became enraged”

- Root: נ־ס־ס (“to be angry / furious”)

- Stem: Peʿal

- Form: Perfect, 3ms

- Meaning: denotes initial outburst of anger

- וּקְצַ֣ף שַׂגִּ֑יא – “and great wrath”

- קְצַף: noun, “wrath/anger”

- שַׂגִּיא: adjective, “great”

The lack of a copula here yields the sense “and (there was) great wrath” or “and he was greatly enraged.”

- וַאֲמַר – “and he said/commanded”

- Root: א־מ־ר (“to say, declare”)

- Stem: Peʿal

- Form: Perfect, 3ms with waw-consecutive

- לְהֹובָדָ֔ה – “to destroy”

- Root: א־ב־ד (“to perish, destroy”)

- Stem: Haphel (causative)

- Form: Infinitive construct with lamed prefix

This is a causative infinitive: “to cause [them] to be destroyed”

- לְכֹ֖ל חַכִּימֵ֥י בָבֶֽל – “all the wise men of Babylon”

- לְכֹ֖ל: “to all” (preposition + kol “all”)

- חַכִּימֵ֥י: “the wise men of” (construct plural of חַכִּים)

- בָבֶֽל: “Babylon” (proper noun, emphatic form)

Syntax of Royal Rage

The structure of the verse is highly compact and reflects formal decree syntax:

- Cause: כָּל־קֳבֵל דְּנָה – “Because of this”

- Emotion: בְּנַ֖ס וּקְצַ֣ף שַׂגִּ֑יא – “He was enraged and [had] great wrath”

- Decree: וַאֲמַר לְהֹובָדָ֔ה – “He commanded to destroy…”

This progression from rationale to emotional escalation to executive command is a characteristic feature of Aramaic royal narrative. The king’s will moves from interior reaction (בְּנַ֖ס) to outward command (וַאֲמַר).

Lexical Note: בְּנַ֖ס vs. קְצַ֣ף

בְּנַ֖ס (from נ־ס־ס) reflects a verb meaning “to become furious” or “to be violently agitated.” It is rare and vivid, distinct from more common wrath verbs.

קְצַף is a more standard noun for “rage” or “anger,” also found frequently in Persian court contexts. Together, they function as a hendiadys expressing total fury: the king became outraged—and it was intense.

Political Function: Lethal Absolutism

Note that the command is not against the specific Chaldeans who failed, but לְכֹ֖ל חַכִּימֵ֥י בָבֶֽל — all Babylonian wise men. This indiscriminate rage and collective punishment is consistent with ancient Near Eastern royal prerogative, where absolute authority could not be undermined without severe consequences.

The Language of Fury

Daniel 2:12 demonstrates how Biblical Aramaic uses compact syntax and verb morphology to narrate dramatic shifts in royal emotion and action. The use of rare verbs like בְּנַ֖ס, the intensified noun-adjective pair קְצַף שַׂגִּיא, and the causative infinitive לְהֹובָדָ֔ה all serve to showcase how grammar and emotion fuse in the Aramaic narrative.

The result is not just a record of fury—it is a grammar of wrath.