From its roots in Phoenician script to its monumental spread across empires, religions, and continents, the Aramaic alphabet stands as one of the most influential writing systems in human history. Functioning as a consonantal abjad with 22 letters, it became the administrative script of the Achaemenid Persian Empire and the foundation for numerous descendant scripts—including Hebrew square script, Syriac, Arabic, and others. Its evolution through styles like Imperial Aramaic and its adoption in sacred Jewish texts such as the Targums and Talmud further cemented its cultural and theological significance. Even today, Neo-Aramaic communities and religious traditions preserve its usage, while modern digital tools sustain its legacy for scholars and scribes alike.

The Alphabet That Shaped a Civilization

The Aramaic alphabet holds a special place in the history of writing and linguistics. As the script of the Aramaic language—a Semitic tongue that became the lingua franca of much of the Near East for over a millennium—it profoundly influenced the writing systems of Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, and even parts of Central and South Asia. The modern Hebrew script used today is in fact a refined descendant of the Aramaic script.

From humble origins as a regional adaptation of Phoenician letters, the Aramaic alphabet spread across empires and faiths. It provided the graphic infrastructure for Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions, leaving its legacy on manuscripts, inscriptions, and sacred texts that continue to shape millions of lives.

Origins: From Phoenicia to Aram

The Aramaic alphabet is an abjad—a writing system that records primarily consonants. It developed from the Phoenician script around the 10th century BC. Arameans, a Northwest Semitic people who settled in modern Syria and northern Mesopotamia, adopted and slightly modified the Phoenician alphabet to suit their own linguistic needs.

As Aramaic-speaking peoples gained political influence—especially after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (612 BC)—their language and script began to spread. With the rise of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC), Aramaic was adopted as the official administrative language, which led to the rapid diffusion and institutionalization of the Aramaic script.

Structure of the Aramaic Alphabet

The classical Aramaic script consists of 22 consonantal letters, just like the Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets. Unlike later scripts such as Arabic and Syriac, the early Aramaic script did not employ extensive diacritical marks or vowel indicators.

Over time, different styles evolved: the original Imperial Aramaic script used in Persian documents, the square script adopted by Jewish scribes (later developing into the Hebrew “Ktav Ashuri”), and the cursive forms that gave rise to Syriac and Nabataean (the precursor of Arabic).

The Aramaic Alphabet Table

| Letter | Name | Pronunciation (IPA) | Transliteration | Modern Hebrew Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐡀 | ʾĀlap | /ʔ/ (glottal stop) | ʾ | א |

| 𐡁 | Bēṯ | /b/ | b | ב |

| 𐡂 | Gāmal | /g/ | g | ג |

| 𐡃 | Dālath | /d/ | d | ד |

| 𐡄 | Hē | /h/ | h | ה |

| 𐡅 | Wāw | /w/, /u/, /o/ | w | ו |

| 𐡆 | Zain | /z/ | z | ז |

| 𐡇 | Ḥēṯ | /ħ/ (pharyngeal fricative) | ḥ | ח |

| 𐡈 | Ṭēṯ | /tˤ/ (emphatic t) | ṭ | ט |

| 𐡉 | Yōḏ | /j/ | y | י |

| 𐡊 | Kāph | /k/ | k | כ |

| 𐡋 | Lāmaḏ | /l/ | l | ל |

| 𐡌 | Mēm | /m/ | m | מ |

| 𐡍 | Nūn | /n/ | n | נ |

| 𐡎 | Semkath | /s/ | s | ס |

| 𐡏 | ʿAyin | /ʕ/ (pharyngeal) | ʿ | ע |

| 𐡐 | Pē | /p/ | p | פ |

| 𐡑 | Ṣādē | /sˤ/ (emphatic s) | ṣ | צ |

| 𐡒 | Qōp | /q/ | q | ק |

| 𐡓 | Rēš | /r/ | r | ר |

| 𐡔 | Šīn | /ʃ/ | š | ש |

| 𐡕 | Tāw | /t/ | t | ת |

The Imperial Aramaic Script and Its Spread

With the expansion of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the Aramaic script and language became tools of imperial administration. Official edicts, receipts, letters, and inscriptions used the Imperial Aramaic script, a standardized version of Aramaic writing that allowed communication across a vast and multicultural empire from Egypt to India.

It was during this time that the Aramaic script left its indelible mark on the Jewish people. By the time the Judeans returned from Babylonian exile in the 6th century BC, they were already adopting the Aramaic script for religious and civil documents. The transition from Paleo-Hebrew to the new “square script” (Ktav Ashuri) began—eventually solidifying during the Second Temple period.

Legacy: Scripts Descended from Aramaic

The influence of the Aramaic alphabet extends well beyond the Arameans themselves. Here are some major scripts directly derived from or influenced by Aramaic:

- Hebrew (Square script) – used in all modern Hebrew texts, originally adapted from Imperial Aramaic.

- Syriac – a liturgical script used in Syriac Christianity, developed around the 1st century AD.

- Nabataean – a cursive form used by the Nabataeans, precursor to the Arabic script.

- Sogdian – an Iranian script used along the Silk Road, important for trade and Buddhist texts.

- Mandaic – used by the Mandaeans, still surviving in small communities today.

- Arabic – although radically transformed, its root shapes can be traced to Aramaic via Nabataean.

Aramaic in Jewish Tradition

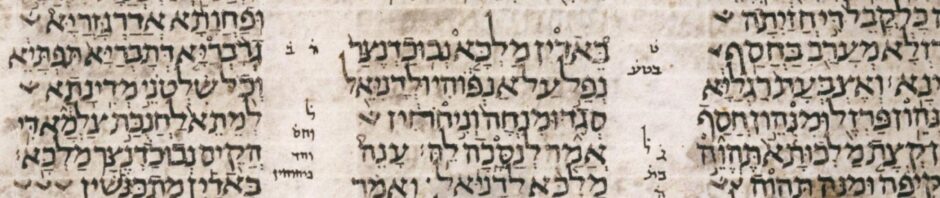

In Judaism, Aramaic became a sacred language alongside Hebrew. Portions of the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Daniel 2:4–7:28, Ezra 4:8–6:18) are written in Aramaic. Key rabbinic works such as the Talmud Bavli, the Targums (Aramaic Bible translations), and mystical texts like Zohar are in Aramaic as well.

Even today, Jewish liturgy includes Aramaic prayers, such as the Kaddish, and the study of traditional texts requires basic knowledge of Aramaic.

Preservation and Modern Relevance

The Aramaic script continues to be used in several contexts:

- Syriac Christianity uses its classical script in liturgy and scholarship.

- Samaritans preserve their own script (a variant of Paleo-Hebrew), but their earlier documents were influenced by Aramaic forms.

- Neo-Aramaic communities, especially Assyrians and Chaldeans, continue to use modern Aramaic dialects and scripts.

Digitally, the Aramaic script has been encoded in Unicode, and fonts are widely available for research and preservation. Epigraphic studies and biblical scholarship heavily depend on understanding Aramaic script development to properly date and interpret ancient manuscripts.

Inscriptions of Influence

The Aramaic alphabet is a pillar in the history of writing. It serves as a bridge between the ancient world of Phoenician merchants, Babylonian scribes, and Persian kings, and the sacred texts of Jews, Christians, and others who used this script to shape theology, law, and culture. Its legacy lives on not only in ancient manuscripts, but in the very letters used daily by Hebrew speakers and liturgical readers of Syriac and Arabic traditions.

In a sense, every scroll of Torah, every copy of Targum, and every page of the Dead Sea Scrolls bears witness to the transformative power of this alphabet that emerged from the heart of the ancient Near East and changed the written world forever.