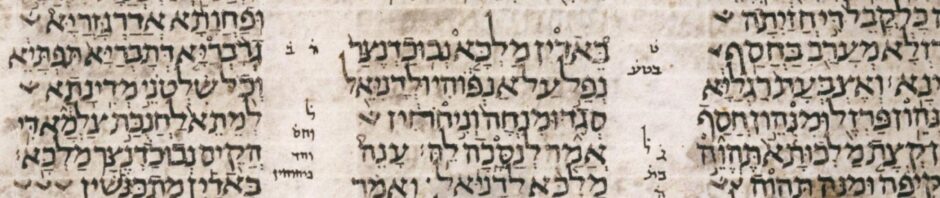

עֲנֹ֥ו תִנְיָנ֖וּת וְאָמְרִ֑ין מַלְכָּ֕א חֶלְמָ֛א יֵאמַ֥ר לְעַבְדֹ֖והִי וּפִשְׁרָ֥ה נְהַחֲוֵֽה׃

(Daniel 2:7)

They answered a second time and said, “Let the king tell the dream to his servants, and we will declare its interpretation.”

A Verse of Repetition and Resistance

Daniel 2:7 marks a critical moment in the Chaldeans’ dialogue with Nebuchadnezzar. Their second answer does not contain new information—it repeats their earlier plea but reframes it subtly. The verse hinges on the use of יֵאמַ֥ר, an imperfect Peʿal verb functioning in a jussive (or volitive) sense: “Let the king say…”

This indirect imperative reveals a common strategy in Biblical Aramaic: when authority is dangerous, language must be cautious. Here, grammar becomes diplomacy.

Morphosyntactic Focus: יֵאמַר (Let him say)

The verb יֵאמַר comes from the root א־מ־ר (“to say”). Morphologically:

- Root: א־מ־ר

- Stem: Peʿal (basic stem)

- Form: Imperfect, 3rd person masculine singular

- Voice: Active (though sometimes stative or modal in nuance)

- Function here: Jussive/volitive – “Let the king say”

Though the form is morphologically an imperfect, its use here is modal: it expresses a wish or command softened by formality. This function mirrors the Hebrew jussive (יֹאמַר) and aligns with how Aramaic handles polite or courtly requests.

Syntax of Request: Indirect Imperative + Coordinated Response

The verse is made of two parallel clauses:

| Clause | Verb | Force |

|---|---|---|

| חֶלְמָ֛א יֵאמַ֥ר לְעַבְדֹ֖והִי | יֵאמַר (Peʿal imperfect 3ms) | Indirect imperative (“Let the king tell”) |

| וּפִשְׁרָ֥ה נְהַחֲוֵֽה | נְהַחֲוֵה (Peʿal imperfect 1cp) | Commitment/future (“We will declare”) |

The Chaldeans’ strategy is syntactic balance: they defer to the king by framing their request as a conditional imperative and offer a clear reciprocal action. “You speak—we interpret.”

Contrast with Biblical Hebrew Usage

In Biblical Hebrew, one might expect a jussive or cohortative construction, such as יֹאמֶר־נָא (“may he please say”). Aramaic, by contrast, makes the imperfect form do more work, especially in modal and volitive senses. This simplicity is not weakness—it’s economy and politeness rolled into one.

The absence of an explicit politeness particle like נָא is notable. While words such as בִּשְׁפֵיר (cf. Daniel 4:24) occur in contexts of politeness or propriety, they are not modal particles in the technical sense. The modal force here lies entirely in the imperfect verb form.

Diplomatic Syntax: When Grammar Shields the Speaker

Why didn’t the Chaldeans just command, “Tell us the dream”? Because this was a dangerous court, not a debate hall. Instead, they used the imperfect Peʿal to cloak their insistence in deference:

- יֵאמַר – avoids imperatives and preserves royal honor

- לְעַבְדֹ֖והִי – “to his servants,” reminding the king of their loyalty

- נְהַחֲוֵה – a cooperative offer: “we will show…”

All this balances survival and subtle subversion.

Grammar as Strategy

When the Chaldeans answered “a second time” (תִנְיָנ֖וּת), they did so with grammar sharpened by fear. The imperfect form יֵאמַר speaks softly but carries strategic weight. By employing the Peʿal imperfect as a jussive, they retained decorum, evaded offense, and masked desperation with syntax.

In Biblical Aramaic, especially in court scenes, survival is often written in the grammar itself.