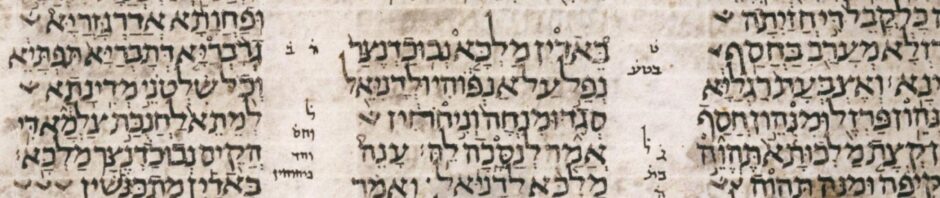

עֲנֹ֥ו תִנְיָנ֖וּת וְאָמְרִ֑ין מַלְכָּ֕א חֶלְמָ֛א יֵאמַ֥ר לְעַבְדֹ֖והִי וּפִשְׁרָ֥ה נְהַחֲוֵֽה׃

(Daniel 2:7)

They answered a second time and said, “Let the king tell the dream to his servants, and we will declare its interpretation.”

Repetition and Resistance: Analyzing יֵאמַ֥ר in Context

In this intense exchange between Nebuchadnezzar and the Chaldean advisors, Daniel 2:7 captures a plea phrased as a respectful demand. The verse’s key grammatical feature lies in the verb יֵאמַ֥ר — a 3rd masculine singular imperfect in the Peʿal stem — which reflects a passive or stative nuance in this context. Though Aramaic often mirrors Hebrew in form, its use of the imperfect Peʿal reveals a subtly different approach to request and obligation language.

Morphological Snapshot: Peʿal Imperfect in יֵאמַ֥ר

The verb יֵאמַ֥ר (“let [it] be said / may [he] say”) derives from the root א־מ־ר (“to say”). Here’s the breakdown:

- Root: א־מ־ר

- Stem: Peʿal (simple active, sometimes passive in imperfect)

- Form: Imperfect, 3rd masculine singular

- Function: Modal/requestive — functioning as a polite imperative: “Let the king say…”

In Biblical Hebrew, the same sentiment would likely use a jussive form or the cohortative with a particle like נָא (“please”). In Aramaic, the imperfect Peʿal without any modal particle can carry this polite, indirect imperative force.

Syntax and Indirect Imperative Force

Let’s examine the two clauses of the verse in relation to verbal form and syntactic structure:

| Aramaic Phrase | Verb | Function |

|---|---|---|

| חֶלְמָ֛א יֵאמַ֥ר לְעַבְדֹ֖והִי | יֵאמַר (Peʿal imperfect) | Polite imperative / optative (“Let the king tell the dream”) |

| וּפִשְׁרָ֥ה נְהַחֲוֵֽה | נְהַחֲוֵה (imperfect Peʿal 1st plural) | Promise in response (“we will declare its interpretation”) |

Notably, the advisors make no demand. They construct their sentence to express willing response—conditional upon the king’s cooperation. This courtly language underscores both fear and strategy.

Historical Nuance and Contrast with Hebrew

Hebrew and Aramaic share many verbal forms, yet their functions often diverge in subtle but important ways. In Hebrew, the 3ms imperfect יֹאמַר can serve jussive or predictive roles, but Aramaic makes greater use of imperfect Peʿal for courtly suggestions or semi-imperatives—especially when no modal particle is present.

In Imperial Aramaic documents (e.g., Elephantine papyri), similar constructions use Peʿal imperfects to voice requests or introduce legally binding stipulations, often in polite or indirect phrasing. This verse in Daniel reflects that same diplomatic register.

Pragmatic Insight: Requests Disguised as Obedience

The advisors begin with עֲנֹ֥ו תִנְיָנ֖וּת — “they answered a second time.” The repetition signals that the pressure is mounting. But rather than issue a counter-threat, they wrap their request in deferential language: “Let the king tell his servants…”

This balance between survival and persuasion is encoded in the imperfect: they do not demand, but they do push. It is grammar as diplomacy.

The Unspoken Negotiation

Daniel 2:7 is not just a sentence—it is a strategic maneuver embedded in grammar. The Peʿal imperfect יֵאמַר conveys a mix of politeness, pressure, and hope. The king’s silence is lethal; their response, carefully calculated. Through imperfect verbs, the servants attempt to buy time, shift the burden, and avoid destruction.

Such subtle distinctions are the heartbeat of Biblical Aramaic—and of political survival.