The Hebrew Tanakh, the foundational religious and literary corpus of ancient Israel, is primarily composed in Biblical Hebrew. However, embedded within its pages are several sections written in Aramaic, a closely related Semitic language that rose to prominence as the lingua franca of the ancient Near East during the Babylonian and Persian periods.

This phenomenon of Biblical Aramaic—the use of Aramaic within an otherwise Hebrew text—has intrigued scholars for centuries. These Aramaic sections appear in specific books and contexts, raising important questions about their purpose, authenticity, and linguistic function. This article explores the presence and significance of Aramaic in the Hebrew Tanakh, identifying each Aramaic passage, analyzing its context, and examining the broader implications for understanding the development of Jewish scripture and identity in antiquity.

Understanding Biblical Aramaic

Aramaic is one of the most widely attested and historically influential languages of the ancient Near East. It was spoken by numerous peoples across Mesopotamia, Syria, and the Levant, and became the dominant administrative language under the Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian empires. By the time of the Babylonian Exile (6th century BC), Aramaic had become the de facto lingua franca of the region, surpassing Akkadian and gradually replacing local dialects—including Hebrew—in many domains.

Biblical Aramaic, as found in the Tanakh, differs somewhat from the classical Imperial Aramaic used in official Achaemenid documents. It shows certain linguistic peculiarities, including morphological and syntactic features that align it more closely with Western Aramaic dialects. Despite these variations, the Aramaic portions of the Tanakh reflect the broader linguistic shift that occurred among the Judeans during and after the Babylonian exile.

The presence of Aramaic in the Hebrew Bible is not merely a linguistic curiosity; it reflects the multicultural and multilingual environment in which parts of the Tanakh were composed. These Aramaic sections may have served to authenticate foreign documents, convey messages to a wider audience, or preserve the speech of non-Israelite characters in a historically accurate manner.

Key Features of Biblical Aramaic

- Vocabulary: While sharing much lexicon with Hebrew, Biblical Aramaic includes distinct terms such as tav (mark) and mareh (seen).

- Morphology: Differences in verb conjugation patterns, especially in the perfect and imperfect forms.

- Syntax: Aramaic often uses a definite article prefixed to nouns (“ha-”), similar to Hebrew, but with some variation in usage.

- Orthography: Though written in the same square Aramaic script used for Hebrew, some orthographic distinctions exist in spelling and vocalization.

List of Aramaic Passages in the Hebrew Tanakh

There are five primary Aramaic sections in the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Tanakh. These include entire chapters, partial narratives, and even just two Aramaic words embedded within a Hebrew verse. Below is a detailed breakdown of each occurrence:

1. Genesis 31:47 – Two Aramaic Words: “Jegar Sahadutha”

In Genesis 31:47, we encounter the only explicit Aramaic expression in the book of Genesis. After Jacob and Laban set up a heap of stones as a covenant between them, Jacob names the heap Galeed (גלעד), meaning “heap of witness” in Hebrew. Laban, however, calls it Jegar Sahadutha (יעגר שהדותא), also meaning “heap of witness,” but in Aramaic.

וַיִּקְרָא לוֹ לָבָן יְגַר שָׂהֲדוּתָא וְיַעֲקֹב קָרָא לוֹ גַּלְעֵד

“And Laban called it Jegar Sahadutha, but Jacob called it Galeed.” (Genesis 31:47)

This brief inclusion likely reflects the Aramean background of Laban, who lived in Padan-Aram, suggesting that the text preserves authentic linguistic detail tied to the characters’ ethnic identities. The dual naming serves both a literary and cultural purpose, highlighting the different cultural and linguistic heritages of the two parties involved.

2. Ezra 4:8–6:18 – Letters and Decrees in Aramaic

The second major Aramaic section appears in the book of Ezra, spanning from Ezra 4:8 to 6:18. This passage contains a series of imperial letters and decrees written in Aramaic, reflecting the bureaucratic nature of the Persian administration. The content includes:

- Ezra 4:8–16: The letter of Rehum the commander and Shimshai the scribe, addressed to King Artaxerxes, warning against the rebuilding of Jerusalem’s walls.

- Ezra 4:17–22: The king’s response, ordering the cessation of construction until further notice.

- Ezra 5:1–6:12: The resumption of temple building under the prophets Haggai and Zechariah, and the subsequent inquiry to King Darius.

- Ezra 6:13–18: The completion of the temple and the celebration of the Passover.

This material was preserved in Aramaic likely because it originated as actual Persian royal correspondence. As Aramaic was the administrative language of the empire, these texts would have circulated in that form. Their inclusion in the biblical narrative suggests that the author or editor wished to present the events with documentary authenticity, using the original language of the source materials.

3. Ezra 7:12–26 – Another Royal Decree in Aramaic

An additional and previously overlooked Aramaic section appears in Ezra 7:12–26, which records a royal decree issued by King Artaxerxes I to Ezra the priest-scribe. This decree grants Ezra authority and resources to lead a group of exiles back to Jerusalem and to reestablish religious and legal order.

דָּתְנָה מִנִּי עַרְתַּחְשַׁסְתְּרָא מֶלֶךְ מֶלְכַיָּא לְעֶזְרָא סָפְרָא דָּלָת תּוֹרַת מָרֵי שְׁמַיָּא הִשְׂכִּימָה׃

“This is a copy of the letter that King Artaxerxes gave to Ezra the scribe, a scribe of the Law of the God of heaven.” (Ezra 7:12)

This passage, like the earlier Aramaic letters in Ezra, represents genuine Persian-era documentation. Its Aramaic composition aligns with the widespread use of the language in imperial administration and underscores the historical accuracy of the biblical account.

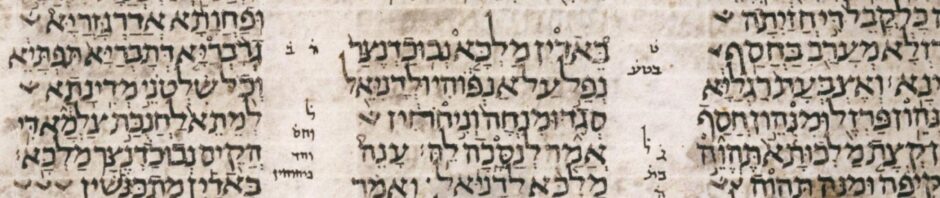

4. Daniel 2:4b–7:28 – Visions and Narratives in Aramaic

The third and longest Aramaic section is found in the book of Daniel, beginning at Daniel 2:4b and continuing through Daniel 7:28. This section includes:

- Daniel 2: Daniel interprets Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of a great statue.

- Daniel 3: The story of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego being thrown into the fiery furnace.

- Daniel 4: The madness and restoration of King Nebuchadnezzar.

- Daniel 5: The writing on the wall at Belshazzar’s feast.

- Daniel 6: Daniel survives the lions’ den ordeal.

- Daniel 7: Daniel’s apocalyptic vision of four beasts rising from the sea.

This Aramaic section may reflect the setting of these stories in the Babylonian and Persian courts, where Aramaic was commonly spoken among officials and interpreters. Furthermore, Daniel 7 marks a transition in genre—from court tales to apocalyptic visions—perhaps indicating a stylistic and thematic shift that coincides with the change in language.

Interestingly, the book of Daniel reverts to Hebrew starting at Daniel 8, possibly signifying a return to native theological discourse after the Aramaic portion, which focused on Gentile rulers and universal themes.

5. Jeremiah 10:11 – A Prophetic Statement in Aramaic

The final and shortest Aramaic passage in the Tanakh appears in Jeremiah 10:11, where the prophet delivers a message directed toward the nations:

כֹּה תֹאמְרוּ לָהֶם אֱלֹהִים אֲשֶׁר לֹא עָשׂוּ הַשָּׁמַיִם וְאֶת הָאָרֶץ מִפְּנֵיהֶם יֹאבְדוּ מֵאֶרֶץ וּמִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמַיִם הָאֵלֶּה

“Thus shall you say to them: ‘The gods who did not make the heavens and the earth shall perish from the earth and from under the heavens.’” (Jeremiah 10:11)

This verse stands out not only for its Aramaic language but also for its polemical tone against idolatry. Scholars believe that this verse was originally intended for a wider, non-Judean audience, possibly as a missionary statement meant to be understood by polytheistic nations who spoke Aramaic as a common tongue.

Its placement within a chapter that critiques idol worship underscores the rhetorical strategy of addressing foreign nations in their own language, thereby ensuring comprehension and impact.

Total Extent of Biblical Aramaic

While the Hebrew Tanakh is overwhelmingly written in Biblical Hebrew, the Aramaic portions constitute approximately 268–269 verses, spread across five distinct passages:

- Genesis 31:47 – 1 verse (2 Aramaic words)

- Ezra 4:8–6:18 – 117 verses

- Ezra 7:12–26 – 15 verses

- Daniel 2:4b–7:28 – 137 verses

- Jeremiah 10:11 – 1 verse

This totals roughly 1% of the entire Old Testament—a small but significant portion that offers unique insights into the historical, linguistic, and cultural evolution of the biblical text.

Historical and Linguistic Implications

The inclusion of Aramaic in the Hebrew Tanakh cannot be viewed in isolation from the broader sociopolitical developments of the ancient Near East. Several key historical and linguistic factors help contextualize the presence of these Aramaic passages:

1. The Rise of Aramaic as a Lingua Franca

From the 9th century BC onward, Aramaic began to spread throughout the Fertile Crescent due to the migrations of Aramean tribes and the expansion of Assyrian military campaigns. By the time of the Babylonian Empire (6th century BC), Aramaic had already gained significant traction as a trade and administrative language.

Under the Achaemenid Persians (539–332 BC), Aramaic was officially adopted as the imperial language, used in royal decrees, legal contracts, and diplomatic correspondence. This explains why the letters in Ezra and the court narratives in Daniel were recorded in Aramaic rather than Hebrew.

2. Cultural and Ethnic Identity

The use of Aramaic in the Tanakh also reflects the complex interplay of cultural and ethnic identity among the Judeans. During and after the Babylonian exile, many Jews became bilingual, speaking both Hebrew and Aramaic. In some cases, Aramaic became the dominant spoken language, as evidenced by post-biblical texts like the Targums, Mishnah, and Talmud.

The inclusion of Aramaic phrases and sections in the Hebrew Bible thus represents a realistic portrayal of the linguistic landscape of the time. It also demonstrates the adaptability of the biblical authors, who could seamlessly switch languages depending on the context and audience.

3. Literary Function and Authenticity

Many scholars argue that the Aramaic sections serve a literary and documentary function, enhancing the perceived authenticity of the text. For instance, the letters in Ezra are presented as genuine imperial documents, while the dialogues in Daniel mirror the multicultural setting of the Babylonian-Persian court.

Similarly, the single Aramaic verse in Jeremiah may have been included to lend weight to its message when addressing foreign audiences. These choices reflect a sophisticated awareness of language and audience on the part of the biblical writers.

Aramaic in Scripture: Historical and Theological Dimensions

The presence of Aramaic in the Hebrew Tanakh is more than a linguistic anomaly—it is a reflection of the historical, cultural, and communicative realities of the ancient world. From the two Aramaic words in Genesis 31:47 to the extensive narratives in Ezra and Daniel, these passages offer valuable insight into the multilingual environment in which the biblical texts were formed.

By incorporating Aramaic into the Hebrew scriptures, the biblical authors acknowledged the shifting tides of power, culture, and communication in the ancient Near East. They also demonstrated a keen sensitivity to audience, medium, and genre, crafting a text that resonated across linguistic boundaries.

In sum, the study of Biblical Aramaic not only enriches our understanding of the Hebrew Bible but also illuminates the dynamic interplay between language, identity, and history in the formation of sacred scripture.