Biblical Aramaic, found in select portions of Daniel, Ezra, and Jeremiah, represents a profound intersection of language, imperial history, and theological expression during the exilic and post-exilic periods. As a dialect of Northwest Semitic origin, closely aligned with Imperial Aramaic, it served both administrative and theological functions in Scripture, offering insight into Jewish life under foreign rule. Its grammar, distinct from Hebrew, enriches comparative Semitic studies and allows for more precise translation and interpretation. Despite a limited corpus, it holds significant relevance for understanding Second Temple Judaism, the linguistic evolution leading to Talmudic literature, and the universalizing scope of divine revelation.

Introduction to Biblical Aramaic

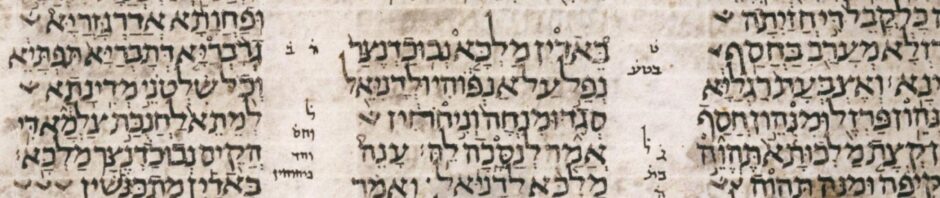

Biblical Aramaic is a distinct form of Aramaic used in specific passages of the Hebrew Bible, representing a unique intersection of language, culture, and theology within the scriptural corpus. While the vast majority of the Tanakh is composed in Biblical Hebrew, several key passages appear in Aramaic, including:

- Daniel 2:4b–7:28: A large prophetic and apocalyptic section.

- Ezra 4:8–6:18; 7:12–26: Official correspondence and royal decrees.

- Jeremiah 10:11: A single verse denouncing idolatry, inserted in Aramaic.

These segments, totaling about 269 verses, reflect the linguistic realities of the Jewish people during and after the Babylonian exile. Aramaic, a Northwest Semitic language closely related to Hebrew, became the lingua franca of the Near East from the Neo-Assyrian period (c. 900 BC) through the early Islamic era. By the 6th century BC, it had largely supplanted Hebrew in daily Jewish life, particularly under Babylonian and Persian rule.

The Linguistic Roots of Aramaic

Aramaic belongs to the Northwest branch of the Semitic language family, which also includes Hebrew, Phoenician, and Ugaritic. It is characterized by its use of emphatic consonants, triconsonantal roots, and a verbal system similar to Hebrew’s. Over time, Aramaic diversified into many dialects, including Imperial Aramaic (used by the Achaemenid Persian administration), Palestinian Jewish Aramaic, Babylonian Jewish Aramaic, and Syriac.

Imperial Aramaic is the dialect closest to Biblical Aramaic. It exhibits orthographic standardization and simplification of morphology, features that facilitated its use across vast administrative regions. The Aramaic of Daniel and Ezra, while exhibiting Hebrew influence, reflects this standardized form, showing its connection to the official language of the Persian Empire.

Why Is Biblical Aramaic Found in the Bible?

The inclusion of Aramaic in otherwise Hebrew texts is not random. It reflects the historical and geopolitical shifts that shaped Jewish life:

- Administrative Context: The Aramaic passages in Ezra, for example, are official letters and decrees. These were likely preserved in their original administrative language.

- Audience Considerations: Daniel’s Aramaic section contains messages directed at a broader, often non-Israelite audience. Aramaic, being the diplomatic and court language, ensured accessibility to imperial readers.

- Linguistic Authenticity: Jeremiah 10:11 is a sarcastic retort to idolaters, delivered in their own common language—Aramaic—to ensure direct confrontation.

This multilingualism reflects a Judaism navigating foreign rule and cultural plurality, adapting its scriptural language to the realities of empire and exile.

Importance of Biblical Aramaic in Biblical Studies

1. Historical Contextualization

Studying Biblical Aramaic opens a window into the exilic and post-exilic periods, particularly during the reigns of Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus, Darius, and Artaxerxes. It reveals how the Jewish community maintained its identity while participating in the linguistic and bureaucratic systems of foreign powers. This is critical for reconstructing the socio-political conditions surrounding the Second Temple period.

2. Philological and Textual Interpretation

Understanding Aramaic enables more precise translations and interpretations of the biblical text. For example:

- Daniel 7:13 speaks of a “Son of Man” (כְּבַר אֱנָשׁ), a phrase that has generated vast theological discourse. The Aramaic phrasing offers specific connotations not fully captured by Hebrew or Greek equivalents.

- Ezra 6:14 refers to the decree of multiple kings. The syntactic construction in Aramaic clarifies whether multiple decrees or a singular proclamation is being discussed—an important distinction in legal interpretation.

Without a grasp of Aramaic grammar, idiom, and syntax, such verses can be misunderstood or misrepresented in translation.

3. Linguistic Shift Evidence

The gradual replacement of Hebrew by Aramaic among the Jewish populace is mirrored in the Scriptures themselves. Biblical Aramaic stands as a fossilized witness to this transition, especially in texts composed during the Persian period. This transition set the stage for the language of the Mishnah and later Talmudic writings, where Aramaic dominates significant portions.

4. Interconnections with Jewish Literature

Biblical Aramaic acts as a linguistic bridge to understanding the broader corpus of Jewish literature. It is the foundational language of the Babylonian Talmud, parts of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Targumim (Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible), and many apocalyptic works such as 1 Enoch and Jubilees. Knowledge of Biblical Aramaic is essential for navigating this extensive body of Second Temple and rabbinic literature.

5. Theological Implications

The Aramaic sections often contain material with significant theological depth. For example:

- Daniel 4 recounts Nebuchadnezzar’s humiliation and confession of YHWH’s sovereignty—an unusual narrative in a foreign king’s voice.

- Daniel 7 contains visionary imagery about divine judgment, messianic hope, and eschatological kingdoms—all in Aramaic.

The fact that these messages were preserved in Aramaic implies an intentional move to universalize their reach beyond Hebrew-speaking Jews. This invites theological reflection on God’s sovereignty over all nations, not just Israel.

Grammar Features of Biblical Aramaic

Although closely related to Biblical Hebrew, Biblical Aramaic exhibits some important grammatical distinctions:

- Definite Article: Aramaic uses the suffix -ā for definiteness (e.g., מַלְכָּא “the king”), unlike Hebrew’s prefix הַ.

- Plural Forms: Masculine plurals often end in -īn (e.g., מַלְכִין), rather than the Hebrew -im.

- Verb System: The Aramaic verbal system employs forms like peʿal (equivalent to Hebrew qal) and paʿel (intensive, like piel in Hebrew), with unique binyan names and patterns.

- Pronouns and Demonstratives: Pronouns are similar but not identical to Hebrew. For example, אַנָא (“I”) vs. Hebrew אֲנִי.

These features require dedicated study but enrich comparative Semitic grammar and aid in understanding Aramaic inscriptions and post-biblical Jewish writings.

Pronunciation and Script

Biblical Aramaic in the Tanakh is written in the Hebrew square script, but it was originally pronounced according to ancient Aramaic phonology. There is ongoing scholarly debate about exact pronunciation, but key features likely included:

- Gutturals like ʿayin and ḥet were pronounced more forcefully than in later Hebrew.

- The emphatic consonants (e.g., ṭ, ṣ, q) had ejective or pharyngealized articulation.

Understanding pronunciation is important not only for reading aloud but also for recognizing wordplay, alliteration, and poetic structure in the original texts.

Challenges in Studying Biblical Aramaic

Despite its limited corpus, Biblical Aramaic poses unique challenges:

- Small Corpus: With fewer than 300 verses, data is limited, making comprehensive grammatical generalizations difficult.

- Textual Corruption: Some Aramaic texts (especially in Daniel) show signs of later editing or textual transmission issues.

- Dialectal Influence: The boundary between Imperial and Biblical Aramaic is not always clear, and some features may reflect scribal traditions rather than vernacular usage.

Nevertheless, its study yields disproportionately rich rewards for biblical scholars, theologians, and linguists alike.

Modern Relevance and Theological Reflection

In modern scholarship, Biblical Aramaic plays a vital role in:

- Intertextual Theology: Themes in Daniel resonate with later apocalyptic texts and the Gospels’ portrayal of the “Son of Man.”

- Second Temple Studies: Ezra’s Aramaic portions inform debates over temple restoration, Persian imperial policy, and Jewish identity.

- Christian Origins: Aramaic continued as a spoken language in first-century Judea, and familiarity with Biblical Aramaic enhances our understanding of the sayings of Jesus and the formation of early Christian texts.

In a theological sense, the inclusion of Aramaic in Scripture reminds us that God speaks through every tongue, and His word is not confined to a single language or nation. The Aramaic segments are not marginal—they are pivotal declarations of divine sovereignty, restoration, and judgment.

Rediscovering a Lost Voice

Biblical Aramaic may be a minority language within the Bible, but its presence is not accidental. It is a witness to the multicultural, multilingual, and multi-imperial world of the Bible. It speaks to the adaptability of God’s people, the reach of divine revelation, and the importance of linguistic and historical context in interpretation.

To study Biblical Aramaic is to rediscover a voice that has spoken across exile, empire, and ages. It is an invitation to listen closely—to the decrees of kings, the dreams of prophets, and the singular truth that transcends language itself.