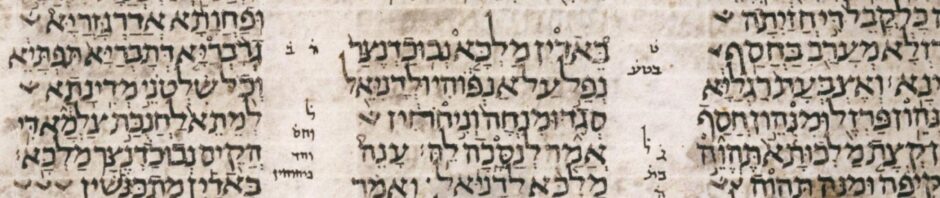

עָנֵ֤ה דָֽנִיֵּאל֙ וְאָמַ֔ר לֶהֱוֵ֨א שְׁמֵ֤הּ דִּֽי־אֱלָהָא֙ מְבָרַ֔ךְ מִן־עָלְמָ֖א וְעַ֣ד־עָלְמָ֑א דִּ֧י חָכְמְתָ֛א וּגְבוּרְתָ֖א דִּ֥י לֵֽהּ־הִֽיא׃

(Daniel 2:20)

Daniel answered and said, “Let the name of God be blessed from eternity to eternity, for wisdom and might are His.”

The verb לֶהֱוֵ֨א (“let it be”) is a striking example of the peʿal imperfect in a jussive sense. Rather than a simple future (“it will be”), the form functions optatively, expressing a blessing: “may His name be blessed.” This nuance is key in Biblical Aramaic doxological formulas, where verbs of being (הֲוָה, “to be”) are employed to convey wishes or declarations of eternal truth.

Parsing לֶהֱוֵ֨א

- Root: ה־ו־י / ה־ו־ה (“to be, to become”)

- Stem: Peʿal (G-stem)

- Form: Imperfect, 3rd masculine singular

- Voice: Active

- Function: Jussive/optative (“may it be”)

- Subject: שְׁמֵהּ דִּי־אֱלָהָא (“the name of God”)

Table: The Function of לֶהֱוֵ֨א

| Form | Stem | Morphology | Nuance | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| יְהֵוֵא | Peʿal | Imperfect, 3ms | Indicative future | “it will be” |

| לֶהֱוֵא | Peʿal | Imperfect, 3ms with prefixed ל | Jussive/optative | “let it be / may it be” |

Wisdom and Might: Possession Marked by דִּי

The closing phrase, דִּי חָכְמְתָא וּגְבוּרְתָא דִּי לֵהּ־הִיא, employs דִּי twice. First, it introduces the causal clause (“for wisdom and might”), then it marks possession (“which are His”). The repetition highlights both the reason for God’s blessing and His exclusive ownership of wisdom and power. The emphatic pronoun הִיא clinches the assertion: it is His, and His alone.

Theological and Linguistic Force

The verse weaves grammar and theology together. The jussive imperfect frames a timeless blessing, while the double use of דִּי structures the logic of praise. Daniel’s response to revelation moves immediately into doxology, and the Aramaic syntax captures both reverence and precision: God’s name ought to be blessed forever, because wisdom and might are not shared commodities but divine prerogatives.

Grammar as Doxology

Here, a single imperfect form (לֶהֱוֵא) transforms a statement into worship. Aramaic grammar allows Daniel to voice eternal praise in a way that is not merely descriptive but aspirational — a call for God’s name to be continually acknowledged. In this sense, grammar itself becomes doxology, as morphology and syntax embody Israel’s confession of divine sovereignty.